Well, maybe not exactly. Located "within the safe environment of a private game reserve," this is "the only Shanty Town in the world equipped with under-floor heating and wireless internet access."

We may jeer, but maybe, in some twisted way, this is part of the mental gymnastics the average Westerner needs to do to understand our relative wealth in its global context.

Hans Rosling has created some fabulous "stats performance" videos to help us. This one from "Don't Panic: The Truth About Population" lays out the daily incomes of the seven billion people alive today along a "yardstick of wealth":

|

| Hans Rosling, "Don't Panic: The Truth About Population" (BBC / Wingspan Productions) |

|

| Hans Rosling, "200 Countries, 200 Years, 4 Minutes - The Joy of Stats" (BBC / Wingspan Productions) |

With an urbanizing and immigrant population bursting the housing capacity of 1909 Toronto, the city had its own shantytowns – one of them right here on Craven Road – as described by Edward Relph in The Toronto Guide: An Illustrated Interpretation of Toronto's Landscapes (p18):

As much as 40 per cent of all the houses constructed between 1900 and 1913 were owner-built, in what Richard Harris has called "unplanned suburbs". The owner-builders acquired a small lot at the end of a new street-car line, put up a wooden shack and then gradually improved it to their own designs as they earned a bit of extra money. The result was a landscape of widely differing houses, irregularly sited on their lots and poorly serviced.

These areas, such as Earlscourt or Craven Road, have matured, but still have distinctive personalities that make them stand apart from the uniform and conformist residential landscapes of the rest of Toronto.The UN HABITAT report The Challenge of Slums explores both the negative and positive aspects of slums. On the negative side, their poor housing conditions include "insecurity of tenure; lack of basic services, especially water and sanitation; inadequate and sometimes unsafe building structures... On the positive side, the report shows that slums are the first stopping point for immigrants... the place of residence for low-income employees... and many informal entrepreneurs [with] clienteles extending to the rest of the city."

Toronto's "shacktowns" of a century ago differed from most modern shantytowns in that homes were put up not by renters or squatters, but by people with a deed to (or a mortgage on) their tiny plot of land. But there were some similarities as well. According to Sean Purdy,

initially they were often poorly constructed one or two room structures with inadequate weather proofing in poorly serviced lots. In the early years, the lack of sewers, water mains, paved roads and public transportation made women's work in the household particularly harsh and burdensome.

Taking advantage of the open spaces and lax regulations, however, suburban families devised clever survival strategies, including growing vegetables, raising livestock and making their own clothing. Moreover, the homes were continually improved by a constant process of rebuilding. The perception remained, however, that the unregulated development of self-built suburbs was an obstacle to efficient city planning.Lawrence Solomon in Toronto Sprawls (p18) writes that these self-sufficient communities

were mostly built on unserviced lots just outside the city limits, to escape the city's high property taxes while enjoying proximity to the city. They also escaped the city regulations that had begun to raise building costs and squeeze out the poor...

This 'shacktown fringe', as a Toronto Globe writer called it, was typically located within walking distance of a streetcar line, and built to high densities. "Shackland's dwellings extend around Toronto," an author wrote in "A Visit to Shackland in Toronto's Suburbs" in 1907. "There is scarcely a terminating car in the city but taps [them]." ...

To meet the demand for housing, the outlying townships permitted rural properties to be subdivided into small lots, making these suburbs attractive to developers and self-builders alike.

|

| Coxwell Avenue, 1912 (Toronto Archives, Arthur Goss, RG 8, Series 18, Item 5) |

On Coxwell Avenue on the city's fringe, a 1912 photo from the City Archives shows three modest ten- to twelve-foot-wide houses tightly built next to each other on lots separated by two-foot-wide lanes, the pattern repeated in other series of houses visible in the background to the photo....Richard Harris in Unplanned Suburbs gives the numbers:

Discussing the impact of the 1904 by-law [inspired by the Great Fire of that year], the Labour Gazette's correspondent noted in 1905 that "many working men are building small houses for themselves beyond the city limits, to escape the stringent regulations forbidding the erection of frame buildings in the city"... Early settlers deliberately chose to live outside city limits in order to have the freedom to build what and how they wished.

Between 1908 and 1913 the average assessed value of dwellings built in the City of Toronto was $1,600, roughly equivalent to a three-bedroom, semidetached brick home with basic services. (This was the assessment for buildings only, excluding land.) In the same period, however, homes were being built much more cheaply in the suburbs, with an equivalent assessed building value of $600. This would have been equivalent to a small frame cottage without services....

In the period 1908-13, "Almost 13 percent of all homes were mere shacks, assessed for less than $250. A substantial number were very modest in size, with a slight peak in the range $500-749...

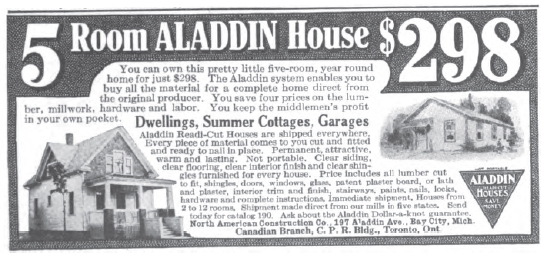

For those who wanted less guesswork and more guidance in the building of their houses, companies such as Sears sold home kits that offered a variety of house plans. These mail-order homes came complete with directions, nails and fixtures, allowing entire houses to be assembled on site.

|

| Aladdin House magazine ad, 1915 |

One morning in the fall of 1913, Alice Randle took a ride to the end of the streetcar line in Toronto's northwestern suburbs. Then she walked north, and immediately, as she later wrote, "the scene ahead began to change.... Before me appeared a vast expanse of little hills and valleys and, here and there... queer shapes of black arose, toy houses they looked like in the distance. It began to dawn upon me now. This must be shacktown, the camp of English immigrants." Up close, she found the homes to be tidy, with "curtained windows [that] showed a thrifty woman's care."

She admired the "romping, sturdy children, quite as immaculate... as gleeful, lung-expanding outdoor games permit." She had mixed feelings about the dwellings themselves. Acknowledging that "each cottage seemed to have a personality all its own," she judged that, to the cultured eye, many of the shacks must seem "ludicrous in size and shape." But she applauded the evidence of hard work and pride which she found about her. Like writers in many other cities at this time, Randle had explored her home turf and had returned with an account of the exotic....

Six years earlier, R. R. Cooke reported in the Toronto Globe that workers were settling all around the city in a broad "shacktown fringe." Soon afterward Arthur Copping, an Englishman who had been commissioned to travel across Canada, visited the Toronto suburb of Earlscourt, probably the same area described by Randle... He explained to his English audience that that families were building their own homes and that "Canadian example encourages a skilful incorporation of the old home within the new. To illustrate the point his brother, Henry Copping, made a watercolour sketch:

|

| The Two Stages of Development in Earlscourt by Henry Copping, in Arthur E. Copping, The Golden Land: The True Story and Experiences of British Settlers in Canada, 1911 |

Workers willingly sacrificed many things that reformers thought they should not, notably privacy and "efficiency," the latter being an all-embracing term used to denote domestic comforts, municipal services, and ready accessibility to centers of employment.... What social scientists missed was the possibility that workers might save money by investing sweat equity in their own dwelling. The geographical implication was obvious. By buying small lots and using their own labor to erect what began as very modest structures, even unskilled workers who worked downtown could afford to settle at the urban fringe.Bill Gladstone republishes on his blog a 1911 article from the Toronto Star, titled "The shantytowns on Toronto’s outskirts," which contrasts the life led by the urban poor in the downtown slums (The Ward) with that in the shacktowns surrounding the city:

The slum-dweller has sewers at his door, but he does not use them, many houses in The Ward having no drain connections. The dweller in the outskirts has no sewers, but he wants them. He is fighting for them, and will get them. Some day, too, he will have good street car facilities, let us hope. In the meantime he has fresh air, and the sanitary conditions in which he lives are as good as those of a small town. The slum-dweller is in a slough of despond. The dweller in the outskirts is making headway towards a competence and is hopeful of the future....

The sight of the little tar-papered shacks they built was at first considered pathetic. Then as the movement grew it was looked upon as ominous. “These people,” it was predicted, “will spoil the outskirts of the city for all time. Conditions will soon be as bad up there as they are in The Ward.” But let us see what resulted....

How much better off is the family of an owner of a little home in the outskirts than that of a man who rents a cottage or cheap rooms downtown? Here is an actual example in comparisons. Two Englishmen in poor circumstances arrived in Toronto a few years ago. Both were painters, with families. They each rented poor rooms in the heart of the city paying about $8 a month. When they had each saved some $30, one man bought a lot in the outskirts, built a shack and moved in. The shackman had his troubles but is getting along. He owns something. He lives in the fresh air. The other man’s wife recently had to pawn her wedding ring to pay their room rent, and they live in one of the places described by Dr. Helen MacMurchy, where one broken, outdoor water-tap serves several families.Electricity, plumbing, sewers, paved streets and sidewalks, the Gerrard streetcar. Craven Road's shacktown in 1909 had none of these. They arrived over the next few decades, but as we'll see in future posts, they didn't come without a fight.

Sometimes the fight was for the new conveniences.

But sometimes, it was against...